YUNYI DAI / NEXTGENRADIO

What is the meaning of

home?

Hunter Vasey speaks with Iran Carlos-Martinez about her experience as a DACA recipient. Iran believes that home is the comfort and support her family provides, even with the threat of deportation.

Family gives a sense of home to DACA recipient

Listen to the Story

Click here for audio transcript

IRAN CARLOS:

My family is my home. Physically, I don’t care where we’re at. I have the best time with them. So it’s them that I love and them that I long for. And if I were to ever get deported, I don’t care where I’m at. It’s knowing that I won’t be with them. That’s what scares me.

I’m Iran Carlos Martinez, and I’m from Belmond, Iowa.

My concept of home in terms of my family is stable. I mean, as a DACA recipient, we’re not really allowed the benefit or the privilege to think of our future for very long.

We’re originally from Rio Bravo, Tamaulipas in Mexico. In Mejico.

And we were just a really young family. I was only nine months old and, my understanding of how we came to the United States is, we actually came legally, so we got permits like visas to come visit.

We just happened to overstay them quite a few years.

So the way I came to know that I was undocumented was in Iowa, any person of the age of 14 is legally allowed to receive a learner’s permit. And, you know, I had some friends that were already doing it.

And so when I approached my parents about it, they were quiet. I don’t remember the exact situation of when they told me, but it always ended with hope. You know, my mom’s like, you can’t do it now because you don’t have papers, but you don’t have to wait for long.

She actually worked with an immigration lawyer.

And so he started giving them advice like, so this is what you should be gathering. This is what you should be preparing for.

And so my mom was really, really good about, she saved every single little paper from the minute I arrived in the United States to the time it was time to apply.

(Iran’s mother speaks) I make one binder with all the pictures y como se dice las calificaciones?

(Iran speaks) The grades.

(Iran’s mother speaks) Yeah, I can show you.

(sound of footsteps)

(sound of binder pages flipping)

This is the binder that my mom send to the government to show them that I am…

(Iran chuckles)

I deserve to be here, no…

This was part of my application, um, to apply for DACA was this binder.

(Sound of binder pages flipping)

My mom, she, we are her world.

My dad definitely, he’s like, you know, you’re gonna do great and amazing things. They definitely believe in us. He also called me his smartest kid.

Don’t tell my sisters. I will be the first person to graduate from my family with a master’s degree. So they’re really proud of that.

Um, Especially when they were still undocumented, they were like, we’re gonna make everything so that anything ever happened to us, you guys will be okay. You know, like, we’re not worried about us. And they always tell me to this day when I’m worried about whatever, what’s happening with DACA.

They’re like, don’t worry about it. We will take care of it.

As common as it is in every immigrant household, we’re all a mixed status family. Um. Both my parents in 2020, very graciously accepted to get their permanent residency.

And then I’m the only DACA recipient and then my two younger sisters are US citizens.

If I were to ever lose my family or like if I were get deported, um, back when 2017 was still happening, those were the darkest times. It definitely got very depressive,.

There was a time, I’ve never told anyone this, but um, I always said like, oh, if I ever get deported, I’d probably just end it.

(Iran pauses)

But I mean, I don’t allow myself to think like that very much, just because it does, it’s horrible to think that way. And I know I probably would never go through with it, I’m not gonna allow myself to think that that’s what’s gonna be my story because it’s not.

This story includes a mention of thoughts of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988. You can also reach a crisis counselor by messaging the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

Iran Carlos-Martinez and her father, Javier, stand outside their family home in Belmond, IA. July 10, 2023.

HUNTER VASEY / NEXTGENRADIO

Belmond is home for Iran Carlos and her family. The Iowa town of 2,500 is where she went to school, ran cross country, and sang in the choir. It’s where she has spent most of her life with her parents and two sisters.

But everything she knows is at risk, because Iran does not have legal permanent status in the country. She fears that she could one day be deported.

“My friends, my family are all here. And to lose all of that, that’s world turning,” she said. “I don’t know if I could cope with that.”

Iran Carlos-Martinez holds her three-legged kitten Estrellita while sitting on her bedroom floor. July 10, 2023.

HUNTER VASEY / NEXTGENRADIO

The Carlos-Martinez family came to the U.S. from Rio Bravo, Tamaulipas, Mexico, when she was only nine months old. The family underwent 20 hours in the backseat of a cramped pickup truck to reach their new home in Iowa. Iran’s mother was eight-months pregnant at the time. But they had family waiting for them in Belmond — who promised them a new kind of life.

“My dad’s sister came with her husband to live in Belmond. When my grandma came to visit, she really just fell in love with the area. It was very quiet, very peaceful, very different from the busy city of Rio Bravo,” Iran said. “My parents were struggling a little bit and she’s, like, you would really like it here . . . and so they were, like, we’ll give it a shot, we’ll see what it’s like.”

“My friends, my family are all here. And to lose all of that, that’s world turning. I don’t know if I could cope with that.”

Iran didn’t learn she was undocumented until she became a teenager. In Iowa, the law states that 14 year olds can receive a license called a learner’s permit, which allows young people to drive while accompanied by an adult over the age of 21. Iran was excited to start driving at the same time as her friends and classmates.

Her parents hesitated.

“I do remember eventually them telling me, like, ‘You know, you can’t do that . . .’ and I remember just asking, ‘Oh, why not?’ And, they kind of said, ‘It’s because you don’t have papers.’”

At first, Iran didn’t worry too much about her undocumented status — but it was never far from her parents’ minds. In 2012, they jumped on a new opportunity that would give her a sense of permanence.

President Barack Obama signed an executive order called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. DACA granted the undocumented children of immigrants legal protection from deportation, as well as the opportunity to work in the U.S. legally. However, the program is not perfect, preventing recipients from leaving the country, and lacking a clear path to citizenship through the policy.

Iran is the only member of her family who is a DACA recipient. Her parents have permanent residency. Her two sisters are U.S. citizens. And as DACA is not a permanent immigration status, Iran’s legal permanence in the country is not a given.

In 2017, former President Donald Trump moved to terminate the program.

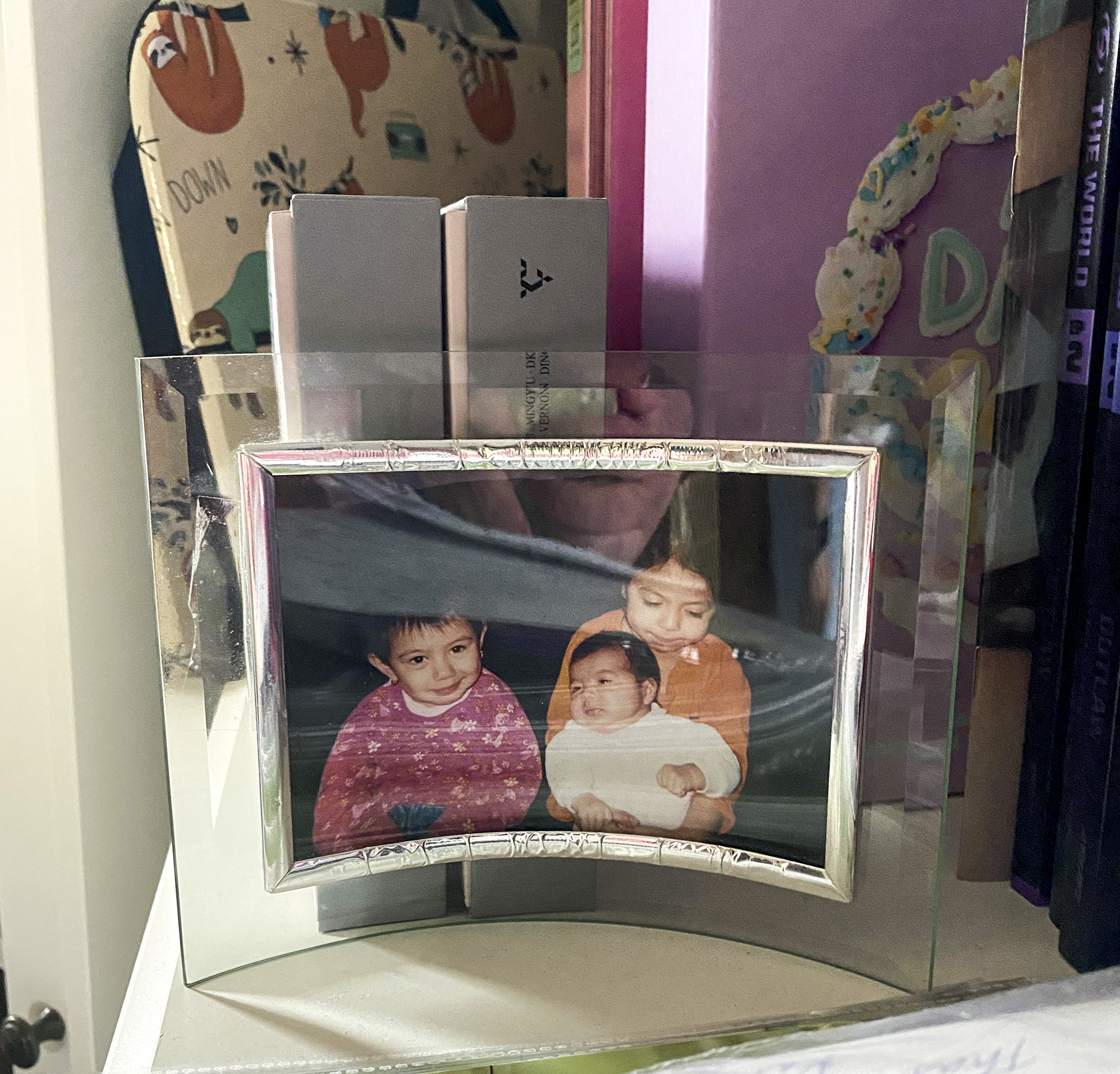

Iran Carlos-Martinez keeps a photo of her and her younger sisters, Kim and Leslie, on her dresser in her bedroom. The photo was taken only a few years after arriving in the United States. July 10, 2023.

HUNTER VASEY / NEXTGENRADIO

For Iran, that was a very dark time. The fear of deportation was never far from her mind. She is comfortable speaking Spanish, but isn’t 100 percent fluent. She hasn’t been to Mexico since they left when she was a baby. And she doesn’t want to leave her family behind. She has some distant relatives in Mexico, but she is not as close to them.

“There was a time, I’ve never told anyone this, but, I always said, like, oh, if I ever have to get deported? I’d probably just end it,” Iran said. “But I’m not gonna allow myself to think that that’s what’s gonna be my story, because it’s not.”

A framed photo of Iran Carlos-Martinez in her high school graduation regalia sits on a shelf just inside the front door of the family home. She is a graduate of Belmond-Klemme High School. July 10, 2023.

HUNTER VASEY / NEXTGENRADIO

Iran isn’t alone in her feelings, according to a study done by the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Rates of suicidal ideation was significantly higher among undocumented individuals (23.1%), and citizens with undocumented parents (24.3%).

Trump’s move to end DACA was blocked by the Supreme Court in 2020. But the policy’s legality is still up for debate. A lawsuit filed by nine states, which does not include Iowa, arguing that the program is unlawful is still making its way through the courts.

Iran is forging ahead in her own life.

In 2020, she graduated from Buena Vista University and is on track to receive her master’s degree from Drake University in Des Moines. Her family has cheered her along every step of her journey, helping her stay on track to success.

“My family definitely very much are my protectors. They are my support system. And so when I think of home, it’s not necessarily Iowa or my house or anything like that. It’s my family.”